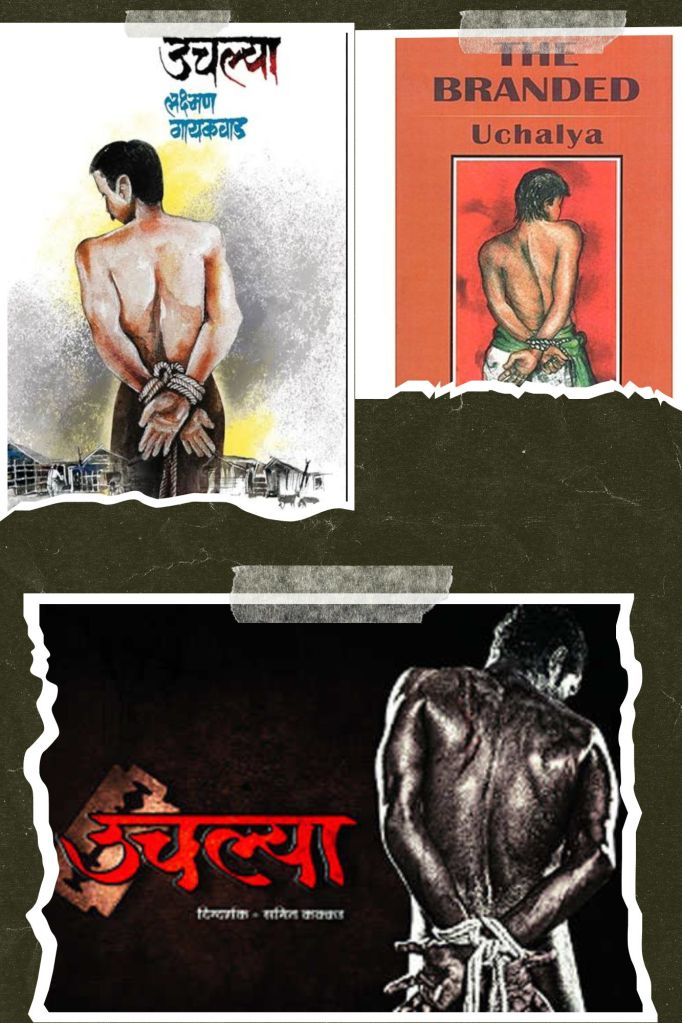

In a land where the wind itself felt raw, sweeping across dust-ridden patches and stirring up tales of survival, The Branded (Uchalya) emerged like a revelation to me. Laxman Gaikwad’s journey took me into a world so distant, yet so close that I could almost feel the grit under my own nails. There I stood, on the periphery of his existence, hovering between his memories and the echo of his ancestors’ footsteps in India’s tribal lands. Gaikwad’s narrative, rooted in the Marathi language but later transformed for a broader audience, plunges deep into his early days, his innocence twisted by the fate of being born into the branded tribe of Uchalya.

Uchalya. A word that in itself seemed as if it were whispered through clenched teeth, spoken with a mix of fear, derision, and perhaps even a dark admiration. A name once imposed upon them by colonial rulers, etched into Indian history under the infamous Criminal Tribes Act. These people were marked, cast aside, declared criminals from birth by an unyielding system that saw only one path for them, and that path was crime. Thieves by trade, their livelihood was both condemned and inescapable. This was not an occupation, but a destiny passed down like a curse.

As Gaikwad takes us through his memories, it becomes evident that for those within Uchalya, “home” was a transient concept. The only constant was hardship. In his words, I could see the dirt floor where children lay at night, with nothing but tattered cloth as their bedding, the barren earth becoming their only support. This small, often urine-soaked patch of cloth was all they had to shield themselves from the biting cold, and in some twisted irony, the trickling warmth of cattle urine would seep into the fibers, offering a brief reprieve from the night’s chill. It was a haunting comfort, a child’s tender relief amidst unspeakable deprivation.

Reading Gaikwad’s recollections of his childhood, I couldn’t help but imagine the cacophony of sounds that must have filled his nights—the distant barking of stray dogs, the murmurs of the tribe, and, occasionally, the heavy thuds of police boots. For the Uchalya, police raids were as routine as the sunrise, an ever-present threat in their lives. The authorities would descend upon them, not seeking justice, but acting on an ingrained suspicion. Searching, always searching, for stolen goods, gold, anything that could serve as evidence against this tribe branded criminal.

Amidst this oppressive routine, Gaikwad’s family dared to dream of something radically different—a school. It was a rare decision, perhaps a revolutionary one, to send him to an actual school. Imagine a young Gaikwad, sitting in a classroom, surrounded by children who had been born into worlds of privilege, whose ancestors were unburdened by labels of criminality. Gaikwad recalls how they would tease him, laughing at his tattered clothes, mocking his origins, reminding him constantly of the boundary between his world and theirs. Even his own tribe eyed him with suspicion. They didn’t understand why anyone would want to break away from tradition, to disrupt the established order by venturing into the unknown.

The book doesn’t spare us the grim details of everyday life in the Uchalya community. Washing clothes was a rare event, a luxury reserved for those times when they wandered close to a river. Otherwise, their attire would stiffen with dirt, and clothes would be hung out to air on their modest rooftops, in an unspoken ritual of endurance. There was no order, no distinction between spaces meant for cooking or resting. In an almost surreal scene, Gaikwad describes open spaces where food was prepared, waste was discarded, and life unfolded all in a chaotic blend. There was no separation between the private and the public, the sacred and the profane.

What strikes me is the paradox that lies at the heart of Gaikwad’s life story. Despite their struggles, despite the indignities endured, the Uchalyas clung to a certain pride. They had nothing to hide; their scars, both literal and figurative, were worn openly, like badges of survival. This unapologetic resilience, their unapologetic poverty—how often do we see such truths laid bare, without romanticization, without apology?

The book is not just an account of Gaikwad’s personal journey but a cultural mirror, forcing readers to confront their own biases. It’s impossible to read his words and not feel the weight of the label “criminal tribe,” imposed not by fate but by the heavy hand of colonial rule. This label shaped every interaction, every law, every possibility. Even the recognition that came much later, when the Marathi version of Uchalya received the Sahitya Academy Award in 1988 and later won the National Award, seems bittersweet. To celebrate Gaikwad’s voice is to acknowledge the grim context that shaped it, to see both the glory and the tragedy entwined.

In Gaikwad’s pages, the Uchalyas rise from the margins and claim space in our consciousness. He asks, perhaps not in words but in the very act of recounting his life: What makes a criminal? Who has the authority to brand an entire people with such a title? Is it birth, is it circumstance, or is it society’s refusal to see beyond labels?

As I close the book, I find myself carrying the weight of Gaikwad’s past, his tribe’s struggles, his defiance in the face of a world that tried to silence him. Through this narrative, Gaikwad becomes not merely a chronicler of his tribe but a voice for all who have been cast aside, for those whose stories are rarely deemed worthy of the page. His words resonate not as mere autobiography but as a testament to survival, resistance, and the enduring human spirit.

#TheBranded #Uchalya #LaxmanGaikwad #IndianLiterature #MarathiLiterature #SahityaAkademiAward #IndianAutobiography #TribalHistory #BookReview #ColonialHistory #SocialJustice #IndianCulture #Bookstagram #ReadingCommunity #LiteratureLovers #TribalStories #Injustice #IndianAuthors

I’m participating in the #TBRChallenge by Blogchatter

Hello. Thanks for visiting. I’d love to hear your thoughts! What resonated with you in this piece? Drop a comment below and let’s start a conversation.