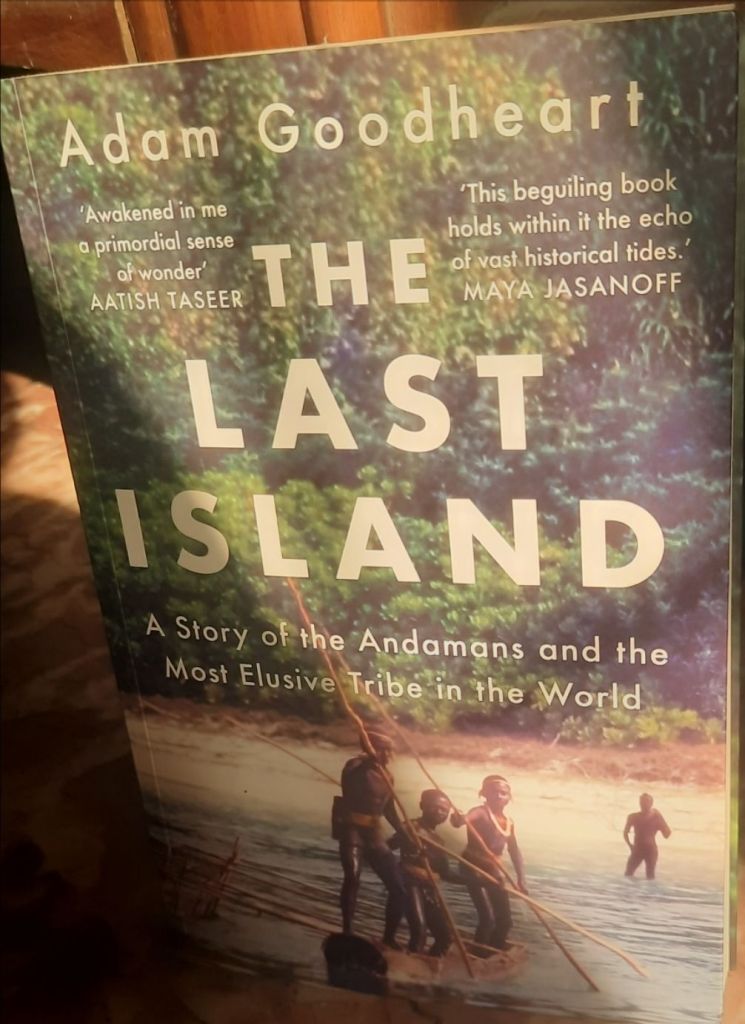

I must confess, reading The Last Island by Adam Goodheart felt less like absorbing a book and more like falling into a profound, pulsating dream—a feverish exploration of history, culture, and the primal force of survival. As I turned the pages, it was as if the narrative pried open an invisible seam in my mind, stitching together distant echoes of forgotten tribes and the haunting modernity encroaching upon them.

Plot: A Mystery Wrapped in Isolation

The book’s essence revolves around North Sentinel Island, that tantalizing speck of land in the Andaman archipelago, where the Sentinelese, one of the last uncontacted tribes, exist beyond the grasp of time and tide. Goodheart’s portrayal of the island is akin to a vivid, surreal painting, its details brushing against my imagination with every stroke—the thick mangrove canopy, the whispers of salt-laden winds, and the silent defiance of a people untouched by the world’s insatiable clamor.

This is not merely a chronicle of an island and its people. It is a palimpsest—layers upon layers of exploration, colonial encounters, anthropological fascination, and ecological marvel—each chapter unfurling like the peeling of an ancient map. The Sentinelese, shrouded in mystery, stand at the story’s core as unyielding sentinels of an uncontacted past, their fierce autonomy a beacon of resistance against the tide of globalization.

Themes: Isolation and the Human Condition

Isolation—how it shapes us, how it defines us—is the heartbeat of this book. As I read, I couldn’t help but wonder: what does it mean to be utterly untouched? Goodheart delves into this existential question with unflinching clarity, presenting the Sentinelese not as relics of a bygone era but as individuals whose way of life challenges our notions of progress. Their resistance to outside contact becomes a haunting metaphor for our collective loss—what have we sacrificed in our relentless march toward interconnectedness?

The ethics of contact—should we intrude, should we protect, should we let them be—weigh heavily on every page. Goodheart does not preach; he prods, stirs, and unsettles. The Sentinelese’s survival is a stark commentary on resilience in the face of oblivion, but it also casts a long, uncomfortable shadow over the history of colonization, the ravages of modernity, and the ethical labyrinths we continue to navigate.

The Characters: Ghosts of Curiosity

The Sentinelese, though elusive, haunt every chapter—their presence visceral and enigmatic, like shadows dancing just beyond the firelight. Goodheart’s brilliance lies in his decision not to anthropomorphize or romanticize them but to respect their impenetrable mystery. It is through the explorers, anthropologists, and government officials that the story takes shape, each character embodying a facet of our fraught relationship with the unknown.

There’s the zealous anthropologist who sees the Sentinelese as a key to humanity’s origins, the colonial officer torn between curiosity and paternalism, the missionary whose faith blinds him to ethical boundaries. These characters, flawed and fervent, are mirrors reflecting our own desires to discover, to understand, to conquer. Goodheart sketches them with empathy yet unflinching honesty, revealing the tensions between intention and consequence.

The Writing: A Dance of Scholarship and Poetry

Goodheart’s prose is not merely writing; it is an incantation. Scholarly yet lyrical, his sentences flow like a river—sometimes calm and reflective, other times a torrent of vivid imagery and poignant insight. I felt the dense jungle pressing against my skin, the primal silence of the island roaring in my ears. Each page is imbued with a sense of wonder and reverence, yet tinged with the melancholy of knowing that even the most isolated places are not immune to the world’s grasp.

He intertwines historical accounts with personal reflections, creating a mosaic that is both intimate and expansive. Anecdotes of past expeditions, tales of shipwreck survivors, and the shadow of colonial exploits are rendered with meticulous detail, yet they never overshadow the central enigma of the Sentinelese.

Ethical Reflections: The Weight of Choice

The most profound impact of this book lies in its ethical undertones. As I read, I felt the weight of our collective choices—the decision to preserve, to intervene, to exploit. Goodheart poses questions that linger long after the book is closed: What right do we have to impose our world upon others? Can isolation be a form of freedom? What does it mean to “leave no trace” in a world where everything leaves a mark?

The book grapples with the paradox of preservation—to protect the Sentinelese is to keep them isolated, yet to make contact is to risk their destruction. It is a dilemma that underscores our own fractured relationship with nature, history, and identity.

Conclusion: A Mirror to Our Souls

The Last Island is more than a book; it is a journey into the heart of what it means to be human. It left me restless, questioning, and strangely hopeful. Goodheart’s masterful narrative is a call to pause, to reflect, to listen to the silence of those who choose not to be heard.

As I closed the final chapter, I felt a peculiar ache—not of longing but of awareness. The Sentinelese remain uncontacted, their island a bastion of solitude in a world consumed by connection. Yet, in their isolation, they have revealed something profoundly universal: the power of choice, the sanctity of culture, and the resilience of the human spirit. In their silence, they have spoken volumes.

I’m participating in the #TBRChallenge by Blogchatter

#TheLastIsland #AdamGoodheart #CulturalPreservation #UncontactedTribes #Anthropology #Globalization #IndigenousRights #IsolationAndSurvival

Hello. Thanks for visiting. I’d love to hear your thoughts! What resonated with you in this piece? Drop a comment below and let’s start a conversation.