Today, we have the privilege of speaking with Madhurima Vidyarthi, a multifaceted talent whose life is a remarkable blend of science and storytelling. As an accomplished endocrinologist trained in Kolkata and London, and a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians (UK), she specializes in adult endocrinology, with a particular focus on the complex interplay of fertility, pregnancy, and diabetes. But Madhurima’s pursuits extend far beyond the medical field.

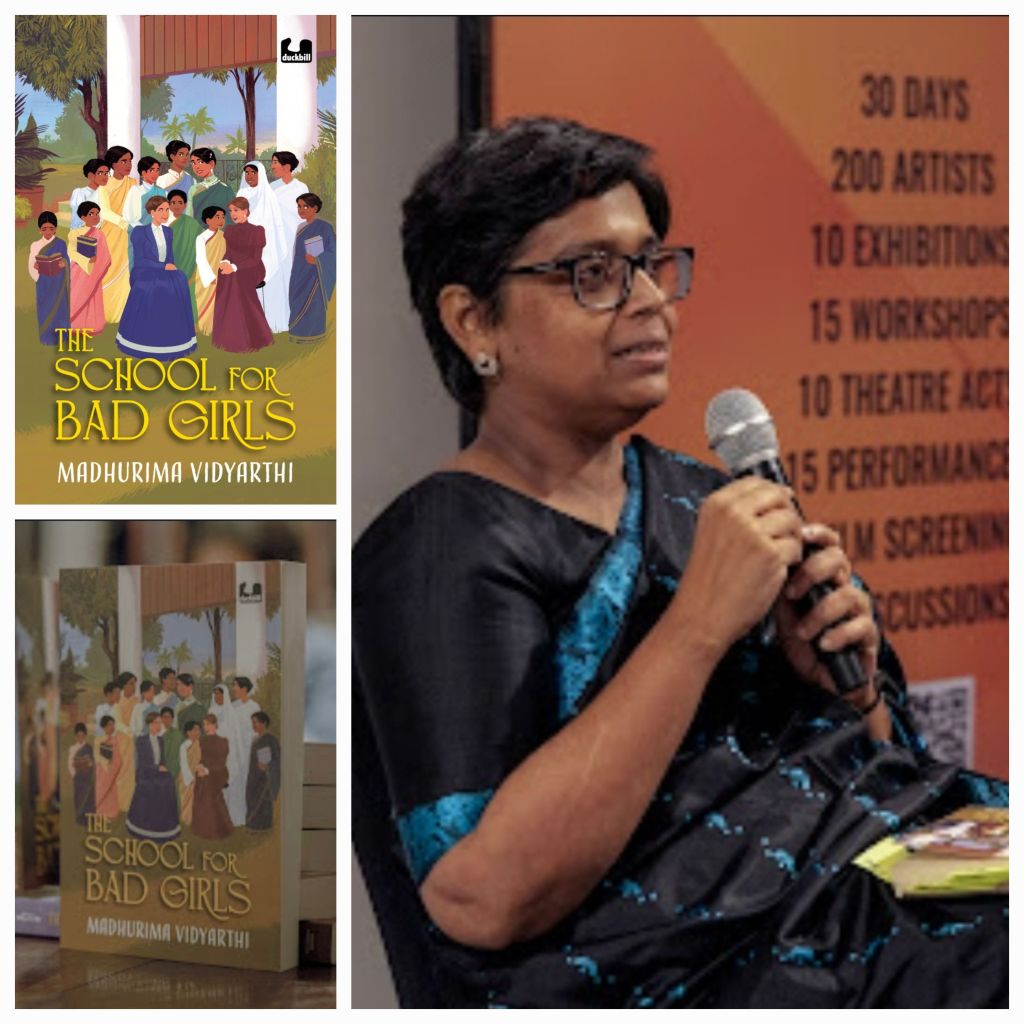

A passionate and versatile writer, she has explored an array of creative formats, from crafting scripts for educational documentaries and multimedia projects to penning fiction that resonates across age groups and genres. Her latest book, The School for Bad Girls (Duckbill, Penguin Random House India), reimagines the women’s emancipation and education movement in India, spotlighting the inspiring story of Kadambini Ganguly, the country’s first woman to train as a doctor. This follows her earlier works, My Grandmother’s Masterpiece (2022) and Munni Monster (2023), and precedes her forthcoming historical novel for adults, slated for release in January 2025.

Let’s dive into a conversation with Madhurima to uncover the inspirations behind her writing, the balance between her medical career and creative endeavors, and the stories she hopes to bring to life.

About The School for Bad Girls

- What inspired you to fictionalize the story of Kadambini Ganguly and the women’s emancipation and education movement in The School for Bad Girls?

MV: As a woman doctor, I wanted to know how it started – I had heard of Kadambini Ganguly but she had not been popularised till the TV series. Her story is so inspiring that it needs to be told again and again. There were so many women that wanted to study and wanted to achieve higher levels of education at that time. It was so interesting that there were some men who helped them as well. The face of India was changing – Bengal especially was changing and being revolutionised.

- How did you approach blending historical facts with fiction to create a compelling narrative?

MV: The aim was to tell a story and a story does not achieve its objective unless someone is asking what happened next. It had to be told and written in such a way that it would be interesting and compelling, and people would want to read and turn the page when they read it. Since it was a historical novel, it had to be true to the history of the time. We went back and forth with editing because there were so many interesting facts that I wanted to put in but could have hampered the narrative and I think that is where the genius of the editor comes in. I was very lucky to have my editor Sharoni Basu of Duckbill and I think she did a great job of pointing out where an info dump was hampering the story.

- Kadambini Ganguly’s journey is one of perseverance against societal odds. How did you craft her character to resonate with modern readers while staying true to her historical context?

MV: Fortunately, or unfortunately, Kadambini has not left a lot of written work about herself like a lot of other people have. There is some research about her, some doctoral papers have been written on her. They are mainly in Bangla; some are in English. I had the great good fortune of being able to contact her great-grandson in Calcutta and he helped me with a lot of family facts, lore, and trivia. The fact that she did what she did, she wrote all the exams and refused to back down gives us a very strong idea of her character and tells us how strong she was. Her activities before and after telling us about her – 10 years after she qualified, she went to England to improve upon her qualifications. She had a large family, she was a practising doctor, she was active in the nationalist movement – so these are hard facts and have been documented in history. It needs a little bit of detective work and a little bit of imagination. With imagination, we can extrapolate back to the seeds of achievement in her as a young girl.

- The title, The School for Bad Girls, is intriguing. What message are you trying to convey through it?

MV: Yes, I had great fun dreaming up her story because I wanted it to be something that would attract the reader’s eye. The name comes from a contemporary newspaper article who called these girls of the Bethune School and The Banga Mahila Vidyalaya ‘bad girls’ because they wanted to study. It’s very interesting to see how the definition of ‘good girls’ and ‘bad girls’ was being turned on its head. These were girls who wanted to study, speak English, go to college and they were called ‘bad’ by a vast number of people in orthodox society. It doesn’t matter which label you are given – you must do what you feel is right. Good and Bad are adjectives that are very relative, and these don’t mean anything. What you want to achieve must be your goal and that is what you must focus on. You shouldn’t get distracted about what people are saying about you.

- The book portrays complex themes like caste, education, and women’s rights. How did you ensure these themes were accessible to a younger audience without diluting their significance?

MV: The most important thing about these themes and a part of the tragedy of these themes are their relevance in the present day and age. The only way to do it is to speak to them as equals and point out your perspective on a certain issue and why you think it is right or wrong. I hope I’ve been able to do that – the book starts with a lot of conversation on gender, caste, education, women’s rights, creed etc.

Historical and Cultural Context

- What challenges did you face while researching 19th-century Calcutta and its social reform movements?

MV: A lot of books have been written and one great challenge was how much to include or incorporate in the book. Many of the books that have been written have included the social and political reforms but there wasn’t that much about the women’s reform movement. What is also absent is our books about domestic lives and we have these very precious narratives by women writers who are adult learners or have become literate in adulthood. There are quite a few narratives about that, and it is very fascinating to go down these wormholes when you want to research the city. What I have found personally useful is to start reading a book about the times and to go into the bibliography and look up those books that have been used as source material. There are also helpful sources online – there are academic websites that give you relevant articles.

- The book features a school where caste is disregarded, a revolutionary idea even today in some contexts. How do you see this theme of equality evolving in modern education?

MV: They are still contemporary themes, and we must speak to children about them. The way people think, speak or act through bias’ is the only way to bring out this bias’.

- How has your medical background influenced your portrayal of Kadambini’s dream of becoming a doctor?

MV: I also faced many challenges as a woman training to be a doctor. I think that it is still unfortunately the case. Deep rooted prejudices in society still make it difficult for women to dream big. I wanted to know how the first women doctors came about and to explore her motivations and the needs of society at that time. It’s also helped me to put in little details of medical training like the portrayal of childbirth which has been described by many readers as a very clinical portrayal. I wanted to do that because these are issues, we tend to avoid in fiction.

Writing Process and Style

- As someone who writes across genres and age groups, how do you adapt your style for children’s fiction compared to other formats?

MV: I think the stories come according to the age groups. I hope that my books have been written in such a way that makes them readable for all age groups and I hope they are enjoyed by them too. Obviously, concepts vary according to age and some subjects may be taboo at a slightly younger age. I am also careful about the language because we need to keep in mind what they say. I try to imagine myself at the reader’s age or pick up references from popular culture.

- What was the most rewarding and the most challenging part of writing The School for Bad Girls?

MV: My most challenging part was writing about being people who were real in history and to make sure I don’t write something that may be objectionable or inaccurate. A lot of these figures still have descendants and families and so I tried to be true to the facts and research material I had. The research and writing were the most rewarding part. Being able to bring to life these characters from history and to be able to see the readers’ reactions was great. I have gotten reactions from people from ages 8 to 80 and they have been very encouraging.

- You’ve worked on scripts, documentaries, and historical fiction. How do these different mediums inform your storytelling?

MV: Scripts and documentaries must be written differently from fiction. They’ve all been a learning process. I have not written a script in a very long time, but I do remember how I wrote scripts for documentaries. I think maybe it makes me want to write a play or part of a book in that format.

Broader Themes and Impact

- How do you think books like The School for Bad Girls can inspire young readers, especially girls, to challenge societal norms?

MV: I hope readers, especially girls, will realize these stories are real. These people were real in Calcutta 150-200 years ago who fought against insurmountable odds to do what they did. I hope that they see that determination, resilience and focus can get them where they want to be. I hope that they realize that there are people willing to help but the effort also has to be made by oneself. I hope boys and girls will reflect on the challenge that society poses for girls and boys in defining their relationship with each other. I hope this will make them think about how they have been conditioned to think.

- The book touches on themes of emancipation and resilience. What parallels do you see between Kadambini’s time and the challenges faced by women today?

MV: The challenges are there, and gender, class, caste, and racial bias are unfortunately still abound. They must be broken, and we have to continue to struggle. A lot of work has been done but a lot of work is still left.

- What role do you believe fiction plays in preserving and interpreting history for future generations?

MV: I don’t know about preserving history as much, but interpreting history is one of the very important roles of fiction. I think it opens one’s eyes to an alternate interpretation of the same history that has been told. Historiography is the writing of history, which can sometimes also include unconscious bias, which is why it is important to read various viewpoints of the same history. In terms of preservation, I think if one is writing about historical fiction, one shouldn’t play around with what has been documented and proven in primary resources. For example, dates, people, and provenance. However, there is room for creative license where there aren’t too many hard facts.

Personal Connection and Future Projects

- Your day job as an endocrinologist and your writing career are quite distinct. How do you balance these two passions, and do they ever intersect creatively?

MV: I hope they do intersect! I do want to write about my life as a doctor in fiction. Perhaps because there is a lot that we see. Other than that, I think they complement each other wonderfully and so I would like to keep doing both as long as I can.

- Do you think initiatives like the AMI Arts Festival help foster a deeper appreciation for art, literature, and history in the community?

- Your upcoming novel for adults, slated for release in 2025, also delves into historical themes. Could you share a glimpse of what readers can expect?

MV: I can only say that it is set in Bengal in the late 17th Century at the end of Aurangzeb’s rule. I’m sorry that is all I am allowed to say at the moment!

- What do you hope readers—both young and old—take away from The School for Bad Girls?

MV: I hope they will take away an inspiration from realisation that history needs to be preserved, repeated, and retold as stories. There are many historical figures who may not be in textbooks but whose contribution to where we are in society is much greater than a handful of so-called celebrated historical figures.

Festival and Audience Interaction

- How do you feel about presenting The School for Bad Girls as part of the Kolkata Centre for Creativity’s AMI Arts Festival?

MV: I am absolutely delighted that I could launch The School for Bad Girls in Calcutta as part of the AMI Arts Festival. I feel it’s a great privilege and I loved working with the AMI team and Priyadarshinee Guha who was a wonderful moderator. I want to be back again very soon!

- What do you enjoy most about engaging with readers during book signings and meet-and-greet sessions?

MV: It’s very heartening to meet readers because you get feedback in real-time from real people who read the book. You get insights and comments that you may not have thought about while writing the book. You also get appreciation which is what we write for.

- Do you think initiatives like the AMI Arts Festival help foster a deeper appreciation for art, literature, and history in the community?

MV: I think initiatives like the AMI Arts Festival are very crucial and I am very pleased KCC is making this an annual event. I hope to see more literature-oriented events at KCC and I’m very happy I could be a part of the 5th edition. I look forward to being there again soon.

In closing, as we drift from the echo of Madhurima Vidyarthi’s words—tracing the vivid lines between history and imagination, between the stethoscope and the pen—it’s clear that her work transcends the boundaries of both fields. The School for Bad Girls is not just a retelling; it is a beacon, a bridge from the past to the present, reminding us that the pursuit of education, equality, and self-realization is timeless. Through Kadambini Ganguly’s indomitable spirit, Madhurima invites us to question the labels society imposes, urging us to redefine what it means to be “good” or “bad.” And, as her narrative unfolds, we are left with the powerful realization that history is never static; it breathes, it evolves, and through the art of storytelling, it finds new relevance in the world we are continuously shaping.

As she continues to weave these compelling tapestries of thought, history, and heart, we eagerly await what comes next. For now, we are reminded of the words Madhurima herself so eloquently expressed: “History needs to be preserved, repeated, and retold as stories.” Indeed, through her work, those stories become the pulse of the present, urging us to continue the dialogue on change, resilience, and the power of narrative in shaping not only our past but our future.

Thank you, Madhurima, for sharing your journey with us. We look forward to seeing where your unique blend of science and art will take us next. Until then, may we all be inspired to find our own “school for bad girls,” challenging the status quo, and turning the pages of our lives with unwavering curiosity and courage.

#MadhurimaVidyarthi #TheSchoolForBadGirls #KadambiniGanguly #WomenInMedicine #IndianHistoricalFiction #EndocrinologistAuthor #DuckbillBooks #IndianWriters #WomenEmpowerment #HistoricalFiction

Hello. Thanks for visiting. I’d love to hear your thoughts! What resonated with you in this piece? Drop a comment below and let’s start a conversation.