Lisa See’s literary universe thrives on forgotten stories. Her latest novel, “Daughters of the Sun and Moon,” arrives in June 2026 with a mission steeped in historical redemption. The book weaves together three Chinese women’s lives. Their survival becomes an act of defiance. Their friendship transforms trauma into resilience. This is See’s 13th novel, and perhaps her most urgent yet.

The Novel’s Hidden Heart

The story opens in 1870 Los Angeles, a dusty pueblo still finding its footing. Three vastly different Chinese women land on American shores. Each carries distinct sorrows and desires. Dove, bound-footed daughter of an imperial scholar, arrives with grace and innocence intact. Her arranged marriage promises wealth and status. Petal, big-footed peasant woman, was sold by her desperate father. She faced second enslavement upon reaching the Gold Mountain. Moon, educated and bilingual, limps from failed footbinding in childhood. Her beauty cannot erase this visible flaw.

These women represent conflicting universes suddenly forced into collision. Dove embodies old-world refinement and privilege eroded by displacement. Petal symbolizes rural poverty, survival instinct, and the price of female servitude. Moon stands at the intersection—educated yet marred, beautiful yet diminished. Together, they navigate what Lisa See calls “eating bitterness,” a concept rooted in Chinese resilience philosophy. This phrase carries weight beyond poetic expression. It describes the art of enduring unbearable hardship.

The Historical Foundation: The Night of Horrors

The novel’s emotional climax centers on an actual historical event. October 24, 1871 changed Los Angeles forever. Historians now recognize this as the largest mass lynching in American history. Approximately 500 white and Latino men attacked Chinatown’s residents. The violence erupted from a territorial dispute between two rival associations. Both groups claimed authority over a kidnapped young woman. One shootout near Negro Alley escalated catastrophically. A white civilian named Robert Thompson died. Rumors spread that Chinese residents murdered him wholesale.

The mob grew ferocious and uncontainable. Seventeen Chinese men and boys died. Some sources indicate eighteen victims, including one buried that very night. Consider the scale: those killed represented 10 percent of Los Angeles’s entire Chinese population. The Chinese community numbered only 172 residents before the massacre. The violence was concentrated, deliberate, and devastating.

Rioters climbed rooftops and fired through holes punctured by pickaxes. Those fleeing were shot point-blank. The Coronel Building served as a temporary fortress. When trapped occupants tried escaping, mobs dragged them to makeshift gallows. Seven bodies hung from John Goller’s portico crossbar. Additional victims were strung from a freight wagon. One historical account describes a rioter pressing a gun to Goller’s face, demanding silence while lynchings proceeded.

The legal aftermath proved hollow. Of the ten men prosecuted, eight were convicted of manslaughter. Yet every conviction was overturned on appeal due to legal technicalities. This outcome embodies American injustice perfectly. The guilty walked free. The community bore permanent scarring.

Footbinding: The Symbol of Displacement

Lisa See employs footbinding as both literal and metaphorical anchor. This ancient practice originated around the tenth century. Legend traces it to Emperor Li Yu’s concubine Yao Niang, who bound her feet into crescent shapes. She danced inside a golden lotus, entrancing her emperor. What began as court performance became status symbol. Later it transformed into cultural identity marker.

By the Qing dynasty, footbinding crossed all social classes. The practice persisted despite Manchu rulers’ multiple banning attempts. Han Chinese viewed it as resistance to foreign dominance. Footbinding paradoxically became proof of cultural superiority. Confucian scholars who initially condemned it later accepted it. Footbinding merged with feminine virtue until separation became impossible.

Young girls endured excruciating bone-breaking procedures. Feet were bound so tightly that bones fractured and reformed. The resulting gait became impossibly constrained, mobility eliminated. Yet bound feet signaled marriageability, refinement, and social acceptability.

See’s character Dove possesses perfectly bound feet. This marks her as educated, elite, and worthy of advantageous marriage. Conversely, Petal’s big feet condemned her to peasant status. Moon’s failed footbinding created lasting limp and social diminishment. Three women, three different relationships with the same oppressive beauty standard. One represents privilege, one represents exploitation, one represents failure. Yet all three faced discrimination in America where footbinding held no cultural currency.

The Author Behind the Story

Understanding Lisa See requires knowing her family foundation. She was born in Paris in 1955 to Carolyn See, a white writer and professor, and Richard See, an anthropologist. Richard’s ancestry traces to Fong See, a legendary Chinese-American businessman. See’s great-grandfather arrived from China in 1871—the exact year her novel begins. That same year witnessed the Chinese Massacre.

See grew up red-haired and freckled in a massive Chinese-American family. Physical appearance conflicted with cultural identity. She was Chinese yet didn’t look Chinese. She belonged yet remained visibly outsider. This duality shaped her artistic sensibility. As See reflects: “Though I don’t physically look Chinese, I am Chinese.” This statement encapsulates her persistent question: Where do I belong?

Her great-grandfather Fong See built an empire starting with ladies’ undergarments before transitioning to Chinese antiques. He married a white woman, Ticie Pruett, when such unions were illegal. They drew up a contract mimicking business partnerships to skirt miscegenation laws. Fong See later returned to China, married a young woman at age 64, and brought her to Los Angeles. The family’s story contained secrecy, illegality, and profound complexity.

See’s debut book “On Gold Mountain” (1995) documented this family history. It became a national bestseller. The research process involved interviewing relatives, excavating family secrets, and contextualizing personal narrative within larger historical movements. See discovered that extensive family material was “illegal, sad and tragic.” Yet telling their story meant honoring forgotten experiences.

Lisa See’s Research Methodology

See’s creative process combines rigorous research with intuitive storytelling. For historical fiction spanning centuries, she cannot interview primary subjects. Instead, she hunts for first-person narratives, personal letters, and contemporary accounts. She travels extensively to visited locations, absorbing atmosphere and cultural nuances. She creates detailed outlines reaching 45 pages before drafting begins.

For “Daughters of the Sun and Moon,” See’s research uncovered the Chinese Massacre deliberately erased from official histories. Few Californians knew about October 24, 1871. Mainstream textbooks omitted it entirely. The incident was deliberately covered up and largely unacknowledged until the twenty-first century. See discovered, researched, and decided this forgotten tragedy deserved resurrection.

Her approach blends archival research, travel, intuition, and family knowledge. She draws on memory, serendipity, and chance encounters. When traveling to Yunnan Province researching adoption and tea, she met a girl who inspired a completely different novel. That willingness to follow unexpected paths characterizes her methodology.

Female Friendship as Resistance

Across See’s body of work, female friendship emerges as central theme. In interviews, she explains her attraction to these relationships. Female friendship differs from any other bond in human experience. Sisters share biological connection. Mothers and daughters navigate generational responsibility. Husbands and wives navigate romantic obligation. Female friendships rest purely on choice, affinity, and mutual understanding.

See explores friendship’s shadow side—its capacity for devastating betrayal. Women tell friends secrets they withhold from mothers, spouses, and children. This creates particular intimacy enabling deepest trust or darkest wounds. In “Daughters of the Sun and Moon,” Moon, Dove, and Petal forged this bond through shared trauma.

The three women didn’t choose connection initially. Hardship and heartbreak bound them together. They witnessed violence targeting their community. They survived when others didn’t. They supported each other through aftermath. Their friendship became survival mechanism, emotional anchor, and revolutionary act. In anti-Chinese Los Angeles, three foreign women could find solace only in each other.

Anti-Chinese Sentiment: American Context

Understanding the novel’s backdrop requires examining anti-Chinese attitudes prevalent in 1870s America. Chinese laborers arrived during California’s gold rush, seeking prosperity. They were welcomed initially as inexpensive labor. When economic downturns arrived in the 1870s, attitudes shifted dramatically.

White Americans began viewing Chinese workers as job thieves and wage suppressors. The “Chinese Question” became political: How could America deal with Chinese laborers supposedly stealing employment? Anti-Chinese activists like Denis Kearney championed the Workingmen Party, ending speeches with “The Chinese Must Go.”

These sentiments culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This legislation suspended Chinese immigration for a decade. Chinese immigrants became ineligible for citizenship. Notably, the act specifically barred Chinese women, preventing settlement and family formation. If Chinese workers couldn’t access wives, they couldn’t build communities. The policy was deliberately designed to eliminate Chinese American presence.

Between 1881 and 1887, Chinese immigration plummeted from 12,000 to just 10 annually. By making Chinese life impossible, America sought ethnic erasure. The 1871 massacre represented violence preceding legal exclusion. It embodied the racial terror undergirding policy.

Why This Story Matters Now

Lisa See insists that her novels answer a singular question: What are the universal human experiences? Across cultures and centuries, people fall in love, marry, bear children, and die. People experience love, hate, greed, jealousy. These universals transcend geography and time. Particularity arrives through customs, traditions, and cultural specificity.

“Daughters of the Sun and Moon” demonstrates that Chinese women experienced the same fundamental desires as all humans. Dove wanted love and beloved status. Petal desired freedom and self-determination. Moon sought justice and agency. These aren’t exotic motivations. They’re profoundly human.

Yet their stories disappeared from American historical record. They were “separated from their families, isolated, and living at the whims of husbands and owners.” Not one arrived by choice. See’s work resurrects their voices from deliberate historical silence. Reading their stories means acknowledging America’s complicity in racial violence. It means recognizing that Chinese-American women contributed to building Los Angeles. It means accepting that their resilience deserves commemoration.

See’s personal connection to this history adds moral weight. Her great-grandparents moved to Los Angeles in 1897, just 26 years after the massacre. Lisa wouldn’t exist without their courage settling near the site of racial terror. As she explains: “My entire extended family wouldn’t be here if not for the courage it took for Fong See and Ticie Pruett to set down their roots just a stone’s throw from where the Night of Horrors began.”

Key Themes Woven Throughout

The concept of “eating bitterness” anchors the narrative philosophically. This Confucian-influenced principle teaches that suffering builds character and resilience. Adversity becomes teacher rather than destroyer. The three women don’t merely survive tragedy—they transform it. Their bitterness becomes nourishment for deeper understanding.

The novel also explores identity fragmentation. Each character exists between cultural worlds. Dove’s refined education means nothing in Gold Mountain. Petal’s peasant strength carries no status. Moon’s education and English fluency cannot overcome her limp. They must learn new languages, adopt new names, navigate foreign social hierarchies. Yet they maintain some connection to Chinese identity even as America denies them belonging.

Footbinding serves as recurring metaphor for bodily autonomy and cultural displacement. Bound feet signified something in China. In America, they became strange, incomprehensible, even monstrous. Cultural practices that conferred value in one context became marks of alienation in another.

The Evening Ahead: Publication and Anticipation

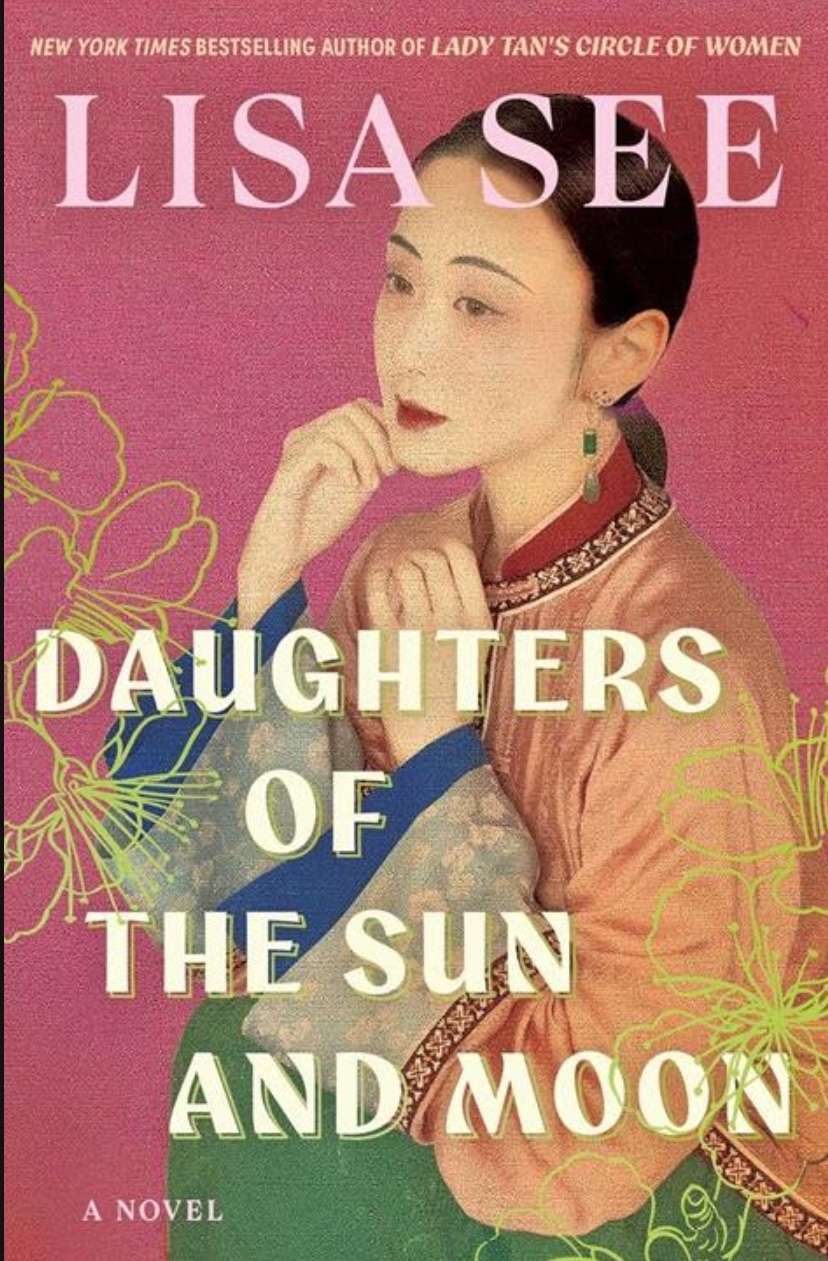

“Daughters of the Sun and Moon” publishes in June 2026. Scribner, an imprint of Simon and Schuster, is releasing it. The cover artwork will be revealed to the public, gradually building anticipation. Lisa See has already begun interviews sharing her research journey.

For readers familiar with See’s previous works, this novel continues her established patterns. It prioritizes female experience. It excavates forgotten histories. It blends meticulous research with accessible narrative. It demonstrates that personal stories illuminate broader historical movements.

Yet this novel feels especially urgent. American political climate increasingly denies marginalized histories. Textbooks continue omitting the Chinese Massacre. Anti-Asian sentiment resurfaces periodically. Telling these stories becomes act of resistance against amnesia. Every book See publishes maintains collective memory.

Summary: Daughters of the Sun and Moon Takeaways

Lisa See’s “Daughters of the Sun and Moon” reclaims three Chinese-American women’s voices from historical erasure. The novel is set in 1870s Los Angeles, centering on the Chinese Massacre of October 24, 1871. This incident killed approximately 18 Chinese residents, representing 10 percent of the Chinese population. It stands as one of America’s largest mass lynchings, yet remained deliberately hidden from mainstream historical record.

See’s three protagonists—Dove, Petal, and Moon—embody different relationships with Chinese culture and American displacement. Their bound or unbound feet symbolize social status, bodily autonomy, and cultural identity. The novel explores how female friendship becomes survival mechanism under conditions of racial violence.

The author’s methodology combines extensive archival research, personal travel, and family history. Her own great-grandfather arrived in 1871, the same year the massacre occurred. This personal connection lends moral urgency to her storytelling. She believes that telling forgotten stories means resisting historical amnesia.

The novel addresses universal human desires—love, freedom, justice—through specifically Chinese-American women’s experiences. It acknowledges America’s complicity in racial violence while celebrating immigrant resilience. It demonstrates that personal narratives illuminate collective histories. Most importantly, it reminds readers that the women who built America deserve recognition and commemoration.

Frequently Asked Questions

When does “Daughters of the Sun and Moon” release?

The novel publishes in June 2026 through Scribner, an imprint of Simon and Schuster. This is Lisa See’s 13th novel.

Is this book connected to Lisa See’s other works?

While each Lisa See novel stands independently, her body of work consistently features female friendships, historical research, and Chinese-American themes. Readers of “Snow Flower and the Secret Fan,” “Shanghai Girls,” or “The Island of Sea Women” will recognize her distinctive style.

What actually happened during the Chinese Massacre of 1871?

On October 24, 1871, approximately 500 white and Latino men attacked Los Angeles’ Chinatown. A territorial dispute between rival associations sparked initial conflict. When rumors spread that Chinese residents killed a white civilian, violence became unstoppable. The mob lynched approximately 17-18 Chinese residents, representing over 10 percent of the city’s Chinese population. The incident was deliberately erased from mainstream historical record.

Why is footbinding significant to the story?

Footbinding was an ancient Chinese practice signifying beauty, refinement, and marriageability. In China, bound feet conveyed high social status. In 1870s America, they became symbols of foreignness and strangeness. The novel’s characters occupy different positions relative to this practice—some bound, some not—reflecting their complex relationships with cultural identity.

Did Lisa See base the characters on real people?

The novel’s three main characters—Moon, Dove, and Petal—were inspired by three real women. Their experiences during the Chinese Massacre and aftermath anchor the narrative, though See exercised creative freedom in developing their individual arcs and relationships.

Why did Lisa See write this particular story?

See discovered this forgotten history during research and felt compelled to resurrect these women’s voices. As a Chinese-American herself, See recognizes that her family wouldn’t exist without brave individuals who settled near the site of racial violence. Her great-grandparents moved to Los Angeles in 1897, continuing to build community despite historical trauma.

Is this appropriate for book clubs?

Yes. Lisa See intentionally writes for book club audiences. Scribner editions include readers’ guides with discussion questions. The novel addresses universal themes—friendship, survival, cultural identity, justice—that generate rich conversation.

Citations:

[1] FEMININITY ASPECT AS REFLECTED IN LISA SEE’S SNOW FLOWER AND THE SECRET FAN https://jurnal-assalam.org/index.php/JAS/article/download/109/98

[2] Living Life as a Text/tile: Animating Asian Americanist Reading Practices https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00447471.2023.2294714?needAccess=true

[3] “Lissa”: An EthnoGraphic Experiment https://journals.umcs.pl/lsmll/article/download/10686/7863

[4] Daughters of the Sun and Moon: A Novel|Hardcover https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/daughters-of-the-sun-and-moon-lisa-see/1148559887

[5] Official Homepage | Official Website of Lisa See https://lisasee.com

[6] Daughters of the Sun and the Moon https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/242100798-daughters-of-the-sun-and-the-moon

[7] Lisa See books in order | Powerful stories of Chinese women https://www.thebookishbulletin.com/blog/lisa-see

[8] New novel release on June 2, 2026 https://www.facebook.com/groups/122673731818386/posts/1803337627085313/

[9] The Daughters of the Moon https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/02/23/the-daughters-of-the-moon

[10] Lisa See’s ‘Daughters of the Sun and Moon’ Highlights … https://people.com/lisa-see-daughters-of-the-sun-and-moon-cover-reveal-exclusive-11834283

[11] Daughters of the Sun and Moon by Lisa See https://app.thestorygraph.com/books/9c6de22b-eb8b-4891-81fa-538ac1f9184c

[12] Book Review: Daughters of the Sun by Ira Mukhoty https://new-asian-writing.com/book-review-daughters-of-the-sun-by-ira-mukhoty/

[13] Daughters of the Sun and Moon | Official Website of Lisa See https://lisasee.com/books/daughters-of-the-sun-and-moon/

[14] The 1871 Anti-Chinese massacre in Los Angeles, and Anti-Asian American antipathies during the COVID-19 pandemic https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/hedn/9/1/9_2021-0006/_pdf

[15] Events that Shaped my Thinking https://managementdynamics.researchcommons.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1171&context=journal

[16] Bubonic Plague https://www.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmj.2.5706.412

[17] Mortality https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10174841

[18] A Quantitative Discourse Analysis of Asian Workers in the US Historical

Newspapers https://arxiv.org/pdf/2402.02572.pdf

[19] A City of Sadness: Historical Narrative and Modern Understanding of History https://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ass/article/download/703/675

[20] Indian “Boarding School” and Chinese “Bachelor Society”: Forced Isolation, Cultural Identity Erasure, and Literary Resilience in American Ethnic Literatures https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/14/4/68

[21] Reviews and Book Notices https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9842358

[22] Oct. 24, 1871: Los Angeles Chinatown Massacre https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/la-chinatown-massacre/

[23] Lisa See’s Lady Tan’s Circle of Women” by Emma Pei Yin https://chajournal.blog/2023/07/03/circle/

[24] Why Footbinding Persisted in China for a Millennium https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-footbinding-persisted-china-millennium-180953971/

[25] The Chinese Massacre of 1871 https://www.lapl.org/collections-resources/blogs/lapl/chinese-massacre-1871

[26] Lady Tan’s Circle of Women by Lisa See https://worldliteraturetoday.org/2024/march/lady-tans-circle-women-lisa-see

[27] Chinese Foot Binding: Radiographic Findings and Case … https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5106533/

[28] Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Los_Angeles_Chinese_massacre_of_1871

[29] An Interview with Lisa See – The Alembic https://alembic.providence.edu/an-interview-with-lisa-see/

[30] Foot binding https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foot_binding

[31] Los Angeles Chinese Massacre of 1871 https://www.britannica.com/event/Los-Angeles-Chinese-Massacre-of-1871

[32] Merging Historical Feminist Fiction-Based Research With the Craft of Fiction Writing: Engaging Readers in Complex Academic Topics Through Story https://journals.library.brocku.ca/brocked/index.php/home/article/download/1126/462

[33] From Historical Fiction to Historical Praxis: Researching Long Eighteenth-Century London’s Black Lives https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03058034.2025.2471648

[34] Fiction for the Purposes of History https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/THEL/article/download/51655/48534

[35] Learning to Live with the Killing Fields: Ethics, Politics, Relationality https://www.mdpi.com/2313-5778/5/2/33/pdf

[36] A Sad Story? Time, Interpretation and Feeling in Biographical Methods https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13575279.2022.2153105

[37] On absence and abundance: biography as method in archival research https://rgs-ibg.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/area.12329

[38] Lisa See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisa_See

[39] It Began With a Family Secret https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000-jun-04-ca-37231-story.html

[40] Discrimination and Exclusion https://pluralism.org/discrimination-and-exclusion

[41] How Lisa See Discovers Untold Stories https://www.altaonline.com/books/fiction/a46996848/how-lisa-see-discovers-untold-stories-anita-felicelli/

[42] Lisa See: “Once it’s Gone, it’s Gone Forever.” https://artsandculture.google.com/story/lisa-see-quot-once-it-39-s-gone-it-39-s-gone-forever-quot-national-trust-for-historic-preservation/xQXxCxLg7awLTg?hl=en

[43] The Chinese Exclusion Act, Part 1 – The History https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/05/the-chinese-exclusion-act-part-1-the-history/

[44] Pre-Modern Chinese Women in Historical Fiction https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/pre-modern-chinese-women-in-historical-fiction-the-novels-of-lisa-see/

[45] NAW Interview with Lisa See https://new-asian-writing.com/naw-interview-with-lisa-see/

[46] Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest https://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/Classroom%20Materials/Pacific%20Northwest%20History/Lessons/Lesson%2015/15.html

[47] Best Selling Novelist Lisa See on her Latest Book and … https://www.how-to-write-a-book.com/best-selling-novelist-lisa-see-on-her-latest-book-and-creative-process/

[48] On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of a … https://apa.si.edu/bookdragon/on-gold-mountain-the-one-hundred-year-odyssey-of-a-chinese-american-family-by-lisa-see/

Hello. Thanks for visiting. I’d love to hear your thoughts! What resonated with you in this piece? Drop a comment below and let’s start a conversation.