Ancient poetry forms whisper from the shadows of history, many now extinct due to the fragility of oral traditions, the collapse of civilizations, and the evolution of languages. These lost voices emerged in the earliest civilizations like Sumer, Egypt, and Vedic India, where poetry served as ritual, memory aid, and communal bond. This article explores their exhaustive details, examples of vanished forms, and how they shaped human expression.

Origins in Earliest Civilizations

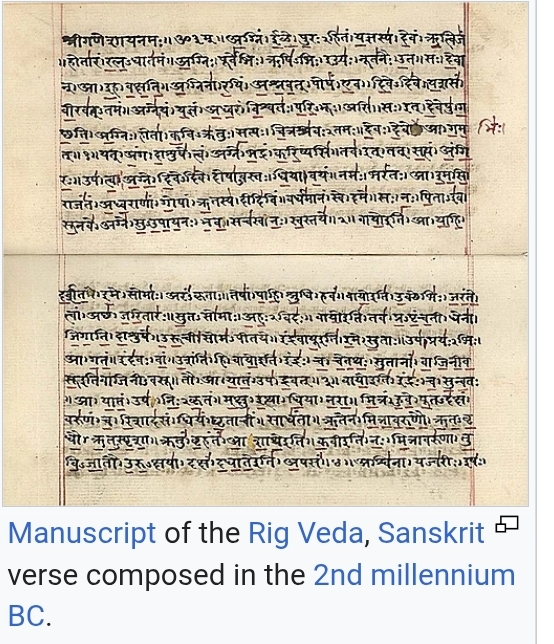

Poetry predates writing, arising in Sumerian Mesopotamia around 3000 BCE as rhythmic incantations etched on clay tablets. Ancient Egyptians followed with Pyramid Texts circa 2400 BCE, blending verse into funerary rites. Vedic seers in India composed the Rigveda (1500–1000 BCE) orally, using mnemonic patterns for cosmic hymns.

Sumerians conversed with poetry through cuneiform, capturing epics like Gilgamesh for eternal recitation. Egyptians inscribed love songs and laments on papyrus, tying verse to Nile rituals. Indo-Aryans chanted Rigvedic stanzas in fire ceremonies, preserving them flawlessly for millennia before script.

Hurrian-Hittite cultures in Syria (1400 BCE) notated songs on tablets, merging music and words in temple praise. These forms vanished as empires fell—Sumerian language extinct by 2000 BCE amid droughts.

Extinct Sumerian Poetry Forms

Sumerian poetry, fully extinct as a living tradition post-2000 BCE, featured line structures adapted to cuneiform’s wedge shapes. Lamentations used repetitive refrains for city destructions, like the Lament for Ur, with parallel lines invoking gods: “Its walls fell, its people scattered.”

Balags, ritual dirges, employed 20-line stanzas with assonance, performed by gala priests in antiphonal call-response. These disappeared with Sumerian speech, surviving fragmented on tablets; their exact intonation lost without native speakers.

Mythological hymns in emesal dialect (priestly women’s tongue) praised Inanna with erotic, rhythmic couplets. No full reconstruction exists; cultural upheaval buried them.

Lost Egyptian Poetic Structures

Egyptian verse, evolving from Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BCE), included Pyramid Texts’ offering spells in parallel bicola: “O King, take the eye of Horus… stand upon the hills.” These funerary forms faded with pyramid-building decline.

New Kingdom love poetry (1300 BCE) used kennings like “sister-lover” in strophic songs on ostraca, but Middle Egyptian hymns in hieratic vanished almost entirely. Demotic love hymns survive singly, their hieroglyphic precursors extinct.

Lamentations for Osiris employed dirge meters with wailing refrains, lost as Coptic replaced hieroglyphs. Temple hymns on walls, rhythmic praises to Amun, crumbled with pharaonic religion.

Vanished Vedic and Indo-European Forms

Rigveda’s oral poetry relied on pada (quarter-verses) in gāyatrī meter (24 syllables), composed by rishis for soma rituals. Pre-Vedic improvisation formulas—stock epithets like “swift-footed”—enabled epic memorization, extinct post-scriptural fixation.

Anuṣṭubh meter (32 syllables, eight syllables per pāda) dominated later Vedas, but archaic ritual chants with pitch accents disappeared orally. Avestan Gathas (Zoroastrian hymns, 1000 BCE) used similar alliterative verses, now ritual-only, their full performative style lost.

Indus Valley seals hint at proto-poetic inscriptions (2600 BCE), undeciphered and extinct.

Hurrian-Hittite and Near Eastern Lost Verses

Hurrian songs from Ugarit (1400 BCE), world’s oldest notated music, praise Nikkal in heptatonic scales with lyrical invocations. Hymn h.6’s 40-line structure, partial lyrics like “greet the lady,” survives incomplete; melody playable but poetic cadence obscure.

Hittite “Song of Ullikummi” epic used unmarked poetic lines with repetitions and assonances, boundaries inferred from clauses. Liberation poems explained Ebla’s fall theologically, bilingual Hurrian-Hittite, extinct with empires.

Akkadian balags influenced Hittites, their cuneiform rhythms tied to lyre accompaniment, unrevivable.

Other Completely Disappeared Forms

Minoan Linear A tablets (1800 BCE) may encode ritual poems, undeciphered and extinct. Elamite hymns (2200 BCE) in linear script, praising gods with repetitive motifs, vanished with empire collapse.

Indus script poetry speculated on seals, potentially mnemonic chants, lost forever. Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions (1850 BCE) suggest Semitic work-songs, fragmentary and extinct.

Olmec Mesoamerican glyphs (1200 BCE) imply chanted myths, pre-Aztec forms gone. Australian Aboriginal songlines, ancient oral cycles, face extinction from colonization.

How Poetry Became Conversant

Early civilizations “got conversant” via orality: repetition, alliteration, and music aided memory in preliterate societies. Sumerians innovated writing poetry first, transitioning communal chants to tablets.

Egyptians integrated verse into magic, reciting Pyramid Texts for afterlife. Vedic Brahmins used śruti (hearing) transmission, 11 recitation modes ensuring fidelity.

Hurrians notated scales, bridging oral to written. Social roles—skalds, rishis, gala—professionalized verse.

Surviving Echoes and Modern Relevance

Fragments like Gilgamesh endure, influencing epics. Lost forms inspire neo-oral poetry.

Digital reconstructions revive Hurrian tunes. For content creators, studying extinctions highlights poetry’s adaptability.

Detailed Examples Table

These lost forms remind us: poetry thrives on adaptation, from clay to code.

Leave a Reply