When the earliest Vedic poets sang of their world, they did not describe abstract kingdoms or fixed borders. They described rivers—roaring, nurturing, disappearing, returning. In their hymns, geography was not background; it was destiny. At the heart of this river-centred worldview lies Sapta-Sindhu, the “land of seven rivers,” remembered as the cradle where early Vedic culture took shape and where some of South Asia’s deepest civilizational layers overlap.

Sapta-Sindhu is not merely a geographical label. It is a cultural memory, preserved across texts, echoed in archaeology, and etched into the shifting courses of rivers themselves. To understand it is to understand how landscape, ecology, ritual, and society co-evolved in the north-western subcontinent.

Meaning and the textual idea of Sapta-Sindhu

The Sanskrit expression Sapta-Sindhu literally means “seven rivers” (sapta = seven, sindhu = river or stream, often specifically the Indus). In the Rigveda, Sapta-Sindhu appears repeatedly as the homeland of the Vedic people—a fertile, river-rich expanse where hymns were composed, rituals performed, and clans moved with seasonal rhythms.

What is striking is that this idea is not uniquely Vedic. In the Old Iranian Avesta, the term hapta-həṇdu (“seven rivers”) appears as well, pointing to a shared Indo-Iranian cultural memory from a time before these traditions fully diverged. This overlap suggests that Sapta-Sindhu was not just a poetic invention but a real, remembered landscape, important enough to survive linguistic and cultural separation.

In both traditions, the “seven rivers” function as more than hydrological facts. They symbolize abundance, order, and divine favor—a world where water sustains life, ritual, and law.

Which seven rivers?

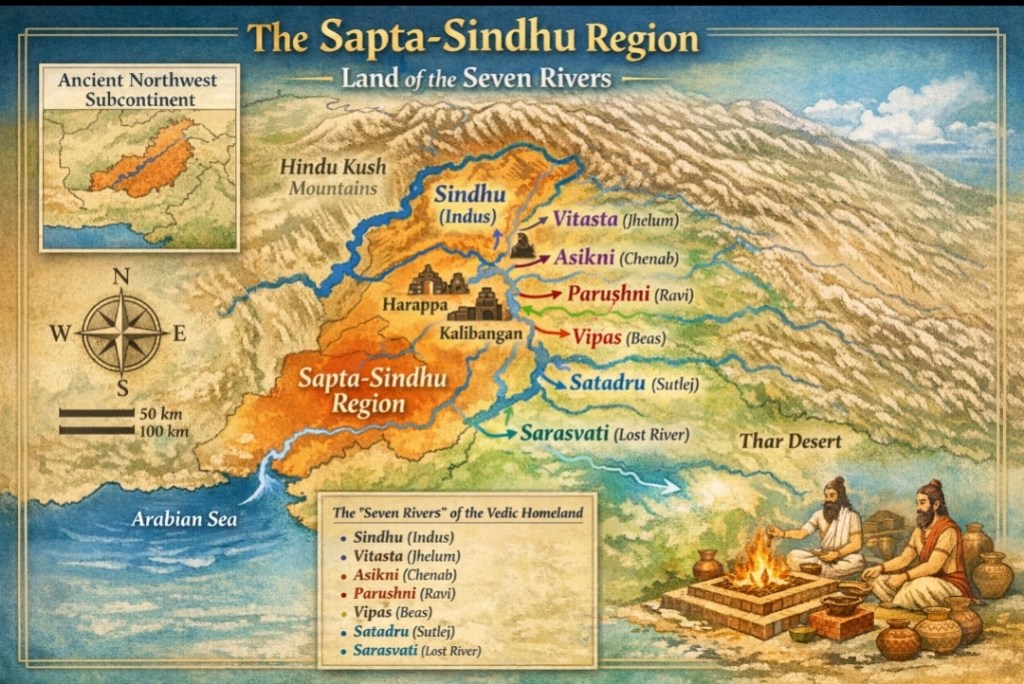

There is no single, uncontested list of the seven rivers. Vedic texts do not provide a neat enumeration, and scholars have long debated how to map poetry onto terrain. However, the most widely accepted reconstruction identifies the following:

Indus (Sindhu)

Jhelum (Vitastā)

Chenab (Asiknī)

Ravi (Paruṣṇī)

Beas (Vipāśā)

Sutlej (Śatadru)

Sarasvati (now largely vanished)

Together, these rivers form the Indus–Punjab–Sarasvati system, spanning today’s eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan.

Some Indian scholars, however, propose a more Sarasvati-centric interpretation, identifying Sapta-Sindhu as Sarasvati plus six tributaries flowing through present-day Haryana—such as the Ghaggar, Markanda, Dangri, and Chautang—arguing that this region was the ritual and cultural heartland remembered most vividly in the hymns.

Rather than seeing these views as mutually exclusive, it may be more accurate to treat Sapta-Sindhu as a fluid riverine cluster, whose precise composition shifted with time, climate, and memory.

The centrality of Sarasvati

Among all rivers of Sapta-Sindhu, Sarasvati occupies a uniquely exalted position. In the Rigveda, she is praised as the greatest of rivers—flowing “from the mountains to the sea,” swift, mighty, and life-giving. Such descriptions exceed what we see today, prompting a long-standing question: Was Sarasvati once a truly major river?

Geological and remote-sensing studies of the Ghaggar–Hakra palaeo-channel suggest that a large river system did indeed flow across Haryana and Rajasthan during the third and early second millennium BCE. This river appears to have been fed by Himalayan sources, including earlier courses of the Sutlej and possibly the Yamuna, before tectonic shifts and river capture redirected these waters.

Later texts remember this decline with remarkable poignancy. In the Mahābhārata, Sarasvati is described as gradually disappearing underground—an image that aligns uncannily well with hydrological evidence of a drying river system. What geology records in sediment and satellite imagery, literature preserves as sacred memory.

Geography and ecological setting

Broadly defined, Sapta-Sindhu encompasses:

- The north-western corridor of the subcontinent

- Snow-fed Himalayan rivers combined with monsoon-dependent tributaries

- Vast alluvial plains capable of supporting dense populations

This ecology made Sapta-Sindhu one of the most agriculturally productive zones of the ancient world. Regular flooding replenished soils, while river networks enabled trade, migration, and cultural exchange.

Importantly, this was not a static landscape. Rivers shifted, channels dried, and settlements adapted. Understanding Sapta-Sindhu therefore requires thinking in terms of dynamic geography, not fixed maps.

Overlap with the Harappan world

One of the most significant insights of recent decades is the deep overlap between Sapta-Sindhu and the Harappan (Indus–Sarasvati) Civilization.

While earlier scholarship emphasized the Indus proper, archaeology now reveals that a very large concentration of Harappan sites lies along the Ghaggar–Hakra–Sarasvati system. Major sites such as Kalibangan, Ganweriwala, and the broader Rakhigarhi region demonstrate that this “vanished river” zone was once a thriving urban and semi-urban landscape.

This has led many scholars to prefer the term “Indus–Sarasvati Civilization”, emphasizing that Harappan urbanism was not confined to a single river but flourished across the Sapta-Sindhu belt.

As the Sarasvati system weakened, settlements reorganized rather than abruptly collapsing. This ecological stress may explain shifts toward smaller, more dispersed communities in late Harappan times.

Rigvedic geography and lived experience

Rigvedic hymns are intensely local. Rivers are named, praised, and invoked as witnesses. The famous Nadī-stuti hymn (RV 10.75) lists rivers in a sequence that maps remarkably well onto north-western geography.

This river-centric worldview suggests that early Vedic society was intimately embedded in its environment. Ritual materials—clay, grasses, firewood—came directly from riverine landscapes. Seasonal movement followed water availability. Even cosmology mirrored hydrology: flow, sacrifice, return.

Later legal-ritual texts such as the Manu Smṛti remember Brahmāvarta, the land between Sarasvati and Drishadvati, as the purest cradle of dharma—a memory rooted firmly in Sapta-Sindhu geography.

Archaeology and cultural continuity

After the decline of urban Harappan centres, cultural life did not vanish. Instead, it transformed.

Painted Grey Ware (PGW) sites emerging after c. 1200 BCE appear precisely in regions once sustained by Sarasvati and later in the Ganga–Yamuna doab. This suggests eastward movement, not rupture—people carrying traditions, memories, and practices forward.

Fire altars at sites like Kalibangan, continuity in settlement locations, and possible transmission of geometric knowledge into later Śulba-sūtra mathematics all hint at long cultural threads linking Harappan and Vedic worlds.

The debate is not whether continuity existed, but how much and in what form.

Scholarly debates and open questions

Despite growing clarity, important questions remain:

- Were the “seven rivers” a fixed list or a symbolic expression of abundance?

- How precisely do Rigvedic composition layers align with archaeological phases?

- To what extent did Harappan urban culture inform early Vedic ritual and society?

What is increasingly clear, however, is that Sapta-Sindhu was not a mythical nowhere. It was a real, lived landscape, remembered, reshaped, and re-imagined across millennia.

Conclusion: a riverine civilizational memory

Sapta-Sindhu represents something rare in human history: a place where ecology, archaeology, and sacred literature converge. Rivers that once flowed across the north-west shaped not only settlements and economies, but ideas of order, divinity, and belonging.

Even after rivers dried and cities transformed, Sapta-Sindhu lived on—in hymns, epics, law codes, and cultural memory. It remains one of the deepest roots of Indian civilization, reminding us that history is not only written in texts or stones, but in watercourses that once carried life, song, and meaning.

Hello. Thanks for visiting. I’d love to hear your thoughts! What resonated with you in this piece? Drop a comment below and let’s start a conversation.