Ancient Ritual Verse, Acoustic Memory, and the Ethics of Listening in a Digital Age

Long before scriptures were frozen into books or monuments hardened into stone, civilizations built their worlds out of sound. Chant, verse, and ritual speech were not decorative additions to belief systems; they were instruments of cosmic alignment, technologies through which humans tuned themselves to divine, natural, and social orders. Across ancient India, Greece, the Islamic world, medieval Europe, and Indigenous societies worldwide, ritual verse functioned as architecture—an invisible structure shaping meaning, memory, and reality itself.

Today, much of this sonic architecture is disappearing. Not because the words are forgotten, but because the conditions that once made them powerful—acoustics, embodiment, transmission lineages, and ritual space—are being transformed or erased. This essay explores ancient ritual verse as a form of sacred architecture, tracing how sound, space, theology, and law converge in both historical practice and contemporary debates about preservation, digitization, and cultural ethics.

Sound as Ontology: When Voice Creates Reality

In many ancient traditions, sound was not a metaphor for truth—it was truth. Ritual verse was understood as ontologically active, capable of shaping relationships between humans, deities, and the cosmos itself. This worldview appears across cultures that otherwise differ profoundly in theology and cosmology.

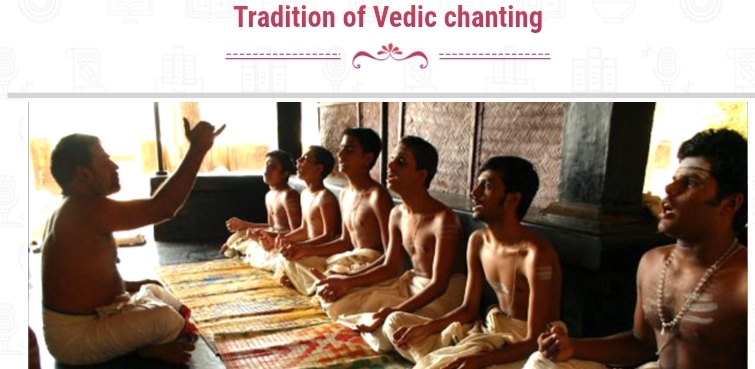

In ancient India, Vedic traditions articulated this most explicitly through the concepts of Śabda-Brahman and Nāda-Brahman, which frame ultimate reality as sound or vibration itself. The universe was not merely described through chant; it was sustained through it. Correct recitation did not symbolize cosmic order—it enacted it.

Similarly, Greek philosophical traditions, especially Pythagorean thought, imagined the cosmos as structured by harmonic ratios. The famed musica universalis, or “music of the spheres,” proposed that celestial bodies moved according to mathematical proportions that produced a form of divine harmony—audible not to the ear, but to the soul. Sound here was the deep grammar of existence.

In Islamic theology, Quranic recitation governed by Tajwid is not treated as musical embellishment but as worship itself. Rules of articulation, rhythm, elongation, and tonal movement are designed to preserve both semantic integrity and spiritual efficacy. Altering sound is not aesthetic experimentation—it risks doctrinal distortion.

Across Indigenous cultures, oral traditions—chants, epics, song cycles—function as living archives of law, history, cosmology, and ethics, transmitted through performance rather than fixed text. Knowledge lives in the voice, the body, and the moment of enactment.

In all these traditions, sound is not secondary to meaning. It is meaning.

The Sonic Architecture of Ritual: Pitch, Metre, Pattern

Sacred sound is never random. Across traditions, ritual verse is built upon highly structured sonic architectures—systems of pitch, metre, rhythm, and formulaic repetition that encode theology as deeply as words do.

Vedic chanting, for instance, employs four primary tonal accents—udātta, anudātta, svarita, and dīrgha svarita—combined with complex recitation paths (pathas) designed to safeguard textual integrity across generations. These systems act as error-correcting codes, ensuring phonetic and tonal accuracy over millennia.

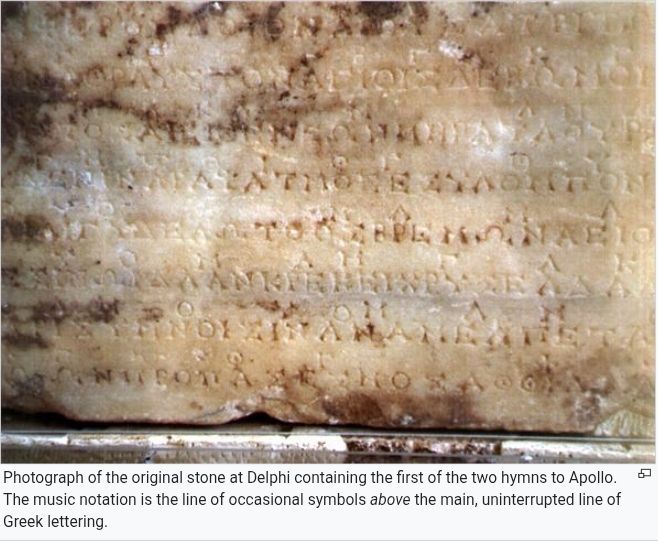

Ancient Greek hymns, such as the Delphic Hymns, integrate linguistic metre (cretic, paeonic, Aeolic), melodic contour, and ritual function into unified sonic forms. Hymnody was inseparable from dance, procession, and spatial orientation within sanctuaries.

Christian Gregorian chant developed as monodic melodic lines precisely suited to the acoustics of stone churches. Long reverberation times encouraged slow tempos, sustained notes, and limited harmonic movement, shaping both music and architecture in tandem.

In Indigenous traditions, formulaic patterns, melodic motifs, and rhythmic cycles often encode genealogies, land rights, and ceremonial law—knowledge that cannot be detached from its sonic form without loss.

These are not merely musical systems. They are sonic blueprints of belief.

Space as Co-Performer: Temples, Cathedrals, and Groves

Sacred sound does not exist in a vacuum. It is co-created by space.

Ritual soundscapes depend on specific environments—temples, cathedrals, mosques, shrines, caves, forests—whose acoustic properties actively shape perception and meaning. In many cases, architecture evolved in dialogue with ritual sound, not independently of it.

Studies of Gothic churches reveal reverberation times often exceeding five seconds at low frequencies. Such acoustics favor monodic chant while constraining rapid speech, reinforcing contemplative listening over semantic clarity. Chant and stone co-evolved.

Similarly, ancient theatres and temples were designed to project voice and song without amplification, embedding ritual audibility into architectural form.

In Indigenous contexts, sacred groves, rivers, and landscapes function as acoustic environments where sound, ecology, and cosmology intersect. Loss of these environments often means loss of ritual coherence itself.

When sacred buildings are renovated, repurposed, or acoustically altered—through tourism, amplification, or conservation choices—communities may experience not just aesthetic loss, but ritual disorientation.

From Oral Worlds to Digital Archives

For most of history, sacred sound was context-bound and ephemeral, sustained through embodied transmission rather than storage. That is rapidly changing.

Recording technologies, digitization, and online platforms have transformed how ritual sound is archived, accessed, and governed. Sacred chants now circulate globally, detached from ritual authority, spatial context, and ethical frameworks.

Heritage science increasingly recognizes soundscapes as intangible cultural heritage, calling for integrated preservation of both architecture and sonic practice. UNESCO’s recognition of Vedic chanting as Intangible Heritage of Humanity reflects this shift.

Digital heritage research now enables scholars to “listen to ancient places” through auralization, impulse-response capture, and audio augmented reality. These technologies allow experimental reconstructions of historical ritual soundscapes—but they also raise questions about authenticity, authority, and consent.

Indigenous revitalization projects increasingly use digital media to document endangered songs, chants, and languages, emphasizing community-led control and ethical governance. Preservation without consent is increasingly recognized as a form of extraction.

Law, Ownership, and the Problem of Sacred Sound

As sacred sound enters digital and commercial ecosystems, legal tensions intensify.

International bodies like WIPO warn that recording and disseminating traditional cultural expressions can strip communities of control, even when intentions are benign. Copyright law, designed for individual authorship and fixed works, struggles to accommodate collective, living, sacred knowledge.

Legal scholarship documents cases where outsiders have copyrighted or patented elements of Indigenous ritual practice—ceremonial songs, shamanic chants—without consent, prompting calls for stronger safeguards and benefit-sharing.

Commercial uses of sacred chants in popular music, wellness industries, or tourism generate revenue but often provoke accusations of commodification, misrepresentation, and appropriation. Sampling culture further blurs boundaries between homage and exploitation.

Ethical debates now include the idea of a “right to future silence”—the principle that communities should retain the ability to withdraw consent and restrict future use of archived recordings, even if technical deletion is difficult.

Ethics of Preservation: Listening With, Not At

Ethnomusicological ethics emphasize ongoing informed consent, respect for ritual boundaries, and negotiation of ownership and access rights. Preservation is no longer understood as neutral documentation, but as an intervention with consequences.

Conservation debates around sacred objects, such as thangkas, argue that maintaining religious significance may require allowing ritual wear, restricted display, or limited access—challenging museum norms of stabilization and openness.

Similarly, transforming fluid oral traditions into fixed digital objects risks reconfiguring authority, authorship, and future interpretive possibilities.

Even well-meaning digital repatriation projects, such as those at the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, must navigate complex negotiations over access, control, and contextual integrity.

AI, Archives, and the Future of Sacred Sound

New debates emerge as AI systems are trained on massive audio datasets, which may include unlicensed sacred or traditional music. Communities often lack mechanisms to opt out, demand attribution, or enforce restrictions.

At the same time, DJs, producers, and community archivists—particularly in Black and Indigenous contexts—have used sampling and mixtapes as forms of radical archiving and teaching, preserving cultural memory even as they expose it to global circuits.

The future of sacred sound thus sits at a volatile intersection of technology, ethics, law, and cosmology.

Conclusion: The Architecture That Still Listens

The “lost architecture” of ancient ritual verse is not merely a matter of historical curiosity. It is a living question about how societies listen, what they value, and who controls the conditions of meaning.

Sacred sound was once inseparable from space, body, lineage, and belief. As it moves into digital systems, it risks becoming everywhere—and nowhere at once.

Preserving sacred sound does not mean freezing it. It means listening with humility, acknowledging that some architectures are meant to resonate, not circulate; to transform participants, not audiences.

The challenge ahead is not only technical or legal. It is ethical:

to decide how sacred sound should live in the present,

and who gets to decide.

Hello. Thanks for visiting. I’d love to hear your thoughts! What resonated with you in this piece? Drop a comment below and let’s start a conversation.